Gastreferat: Prof. Christopher Lupke: "Decoding the Laconic Obscurity of Post-Martial Arts Cinema"

09/21/2016Wir laden alle Studierenden und Interessierte herzlich zum Gastvortrag "Decoding the Laconic Obscurity of Post-Martial Arts Cinema: Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin and the Modern Female Knight-Errant" von Prof. Christopher Lupke der University of Alberta, Chair of Department of East Asian Studies, ein.

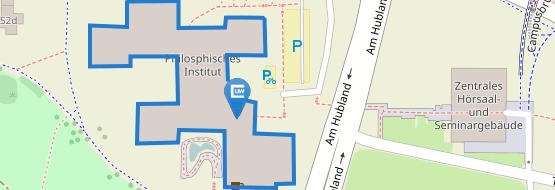

Der Vortrag findet am 29. September 2016 um 16:00 Uhr im Übungsraum 17, Philosophiegebäude statt.

Abstract

Hou Hsiao-hsien’s first film in eight years, The Assassin, has been met by critics and popular audiences with what has now become their customary perplexity. The extreme understatement through the use of ellipsis editing has become one of the hallmarks of Hou’s work. Unable to decode the narrative, many of the reviews and much of the commentary on it resort to discussions of its visual beauty, in a respect a sort of inverse parallel to that lavished upon his 1998 film Flowers of Shanghai. Whereas Flowers recorded the plethora of interior opulence that adorned brothel culture in late Qing dynasty Shanghai, the camera’s gaze in The Assassin lingers upon the natural outdoor scenery of the Tang upon which the exquisite set and costume design are inlayed.

But the beauty of the film may be a diversion from the luminous though laconic plot structure, which through scrutiny reveals a total rewriting of the traditional Chinese narrative trope of the female knight errant. The conventional knight errant in Chinese narrative, including some prominent female examples, comprises a few key elements: a cold-hearted lack of affect; an indomitable loyalty to one’s liege; expert lethal technique; and a lifestyle on the social margins. This is almost true of the original Nie Yinniang on which the film is loosely based, as well as the complementary character Hong Xian in another Tang Dynasty classical tale that also inspired the depiction of Hou’s heroine.

This talk investigates the original narratives from the Tang Dynasty, comparing them to Hou’s film, and incorporates into it an analysis of discussions about the development of the film by screenwriters Xie Haimeng, Zhu Tianwen and director Hou Hsiao-hsien. Noting what Xie has said, the essay also looks at the vernacular huaben narrative “Madame Bai Forever Imprisoned under Thunder Peak Pagoda,” for it echoes the solitude of unrequited or interrupted love deeply submerged in the text of Hou’s film.